February 2022 Five Ways to Enhance Safe Fecal Sludge Management in Urban, Low-income Areas Vanessa Guenther, Karen Setty, and Rachel Peletz

Photo Credit: The Aquaya Institute

February 2022 Five Ways to Enhance Safe Fecal Sludge Management in Urban, Low-income Areas Vanessa Guenther, Karen Setty, and Rachel Peletz

Densely populated areas unserved by sewer systems continuously produce fecal sludge, for which safe disposal or recycling is challenging to achieve at scale. A group of researchers from the Aquaya Institute, Oliver Wyman, and Great Lakes University of Kisumu collected evidence and recommendations from Kisumu, Kenya.

Background

Located in Western Kenya and bordering Lake Victoria, Kisumu is the country’s third-largest city with an estimated 419,000 inhabitants, of which approximately 60% live in low-income, informal housing settlements.

Fecal sludge management is required in densely populated areas where part of the population is not connected to a sewerage system. In Kisumu, sewer services are only available to a small and decreasing proportion of the population, as local government investments cannot keep up with explosive urban growth. Consequently, disposing of fecal sludge is a constant concern for the low-income residents of Kisumu. If service cannot be arranged in a timely and affordable manner, latrines may overflow and become unusable, causing safety concerns, odors, and reduced sanitation access.

Residents are often driven to use informal service providers. Roughly 70% of households in Kisumu rely on latrines constructed over simple pits. Periodically emptying these pits can be difficult due to the limited availability of ‘formal’ manual emptying organizations or vacuum trucks that can access dense urban settlements, remove solid waste, and are affordable. Therefore, residents are forced to use unregulated, informal service providers that often dispose of fecal waste using unsanitary and unsafe methods.

Typically, these pits are either emptied by vacuum truck operators (VTOs), who charge more and mainly serve wealthier households or informal manual emptiers who remove fecal sludge by hand or buckets. Both service providers may bury sludge onsite or dispose of it in nearby waterways. This unregulated dumping by both providers leads to the pollution of surface and groundwater, the spread of pathogens in the environment, and adverse public health effects.

Only one-third of the fecal sludge generated in the city is estimated to be safely collected and treated.

Increasing the use of safe and regulated emptying services that ultimately treat or recycle waste is critical for improving Kisumu’s sanitation situation.

Manual pit emptiers at work. Photo Credit: The Aquaya Institute

The Study Design

Aquaya Institute aimed to compare the financial structures of existing formal manual emptying organizations and VTOs to better understand the feasibility of expanding safe fecal sludge services to low-income areas.

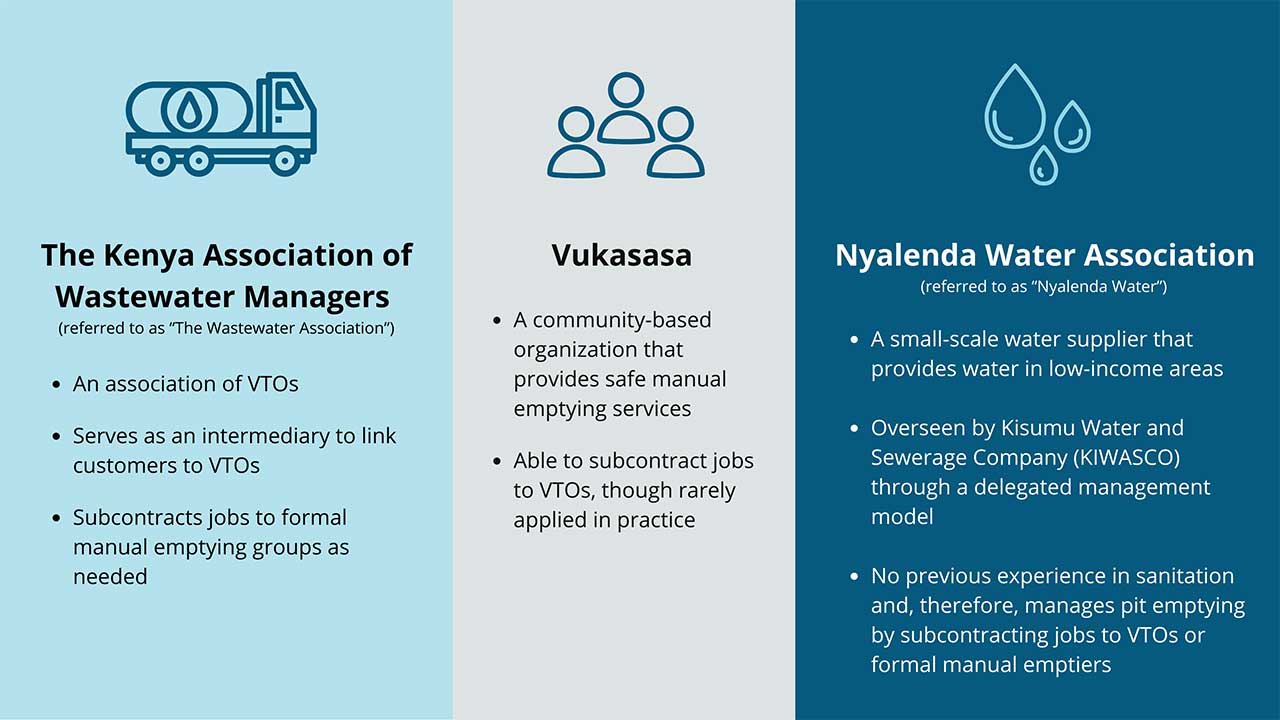

Aquaya engaged three groups for fecal-sludge management: a VTO (The Wastewater Association), a community-based organization that provides safe manual emptying services (Vukasaka), and a small-scale water supplier (Nyalenda Water Association). Throughout the study, these three selected groups continued to manage the delivery of safe emptying services within their separate geographical areas of Kisumu. They were responsible for marketing services, identifying customers, setting prices, coordinating pit-emptying jobs, and subcontracting jobs as needed.

Photo Credit: The Aquaya Institute

To encourage study participation, Aquaya provided a 3,000 KES (30 USD) cash incentive to the groups for each emptying job completed within their respective geographical zones. Aquaya also provided a 2,000 KES (20 USD) cash incentive per trip to transport the fecal sludge to Kisumu Water and Sanitation Company’s treatment site. Aquaya established these prices in collaboration with the managing groups to ensure these activities were profitable.

For each group, Aquaya collected data to assess: (i) safe emptying performance, (ii) financial performance, and (iii) customer satisfaction.

Five insights from the Kisumu case study

The economic analysis showed that the VTO group (the Wastewater Association) was about four times more cost-effective than the formal manual emptying organization and was most efficient in providing emptying services to poor households. The Wastewater Association also received the highest customer satisfaction ratings and maintained the most reliable records of business activities.

1. Consider vacuum truck operators (VTOs) as a viable option

The economic analysis showed that the VTO group (the Wastewater Association) was about four times more cost-effective than the formal manual emptying organization and was most efficient in providing emptying services to poor households. The Wastewater Association also received the highest customer satisfaction ratings and maintained the most reliable records of business activities.

2. Carefully choose and support the managing organization(s)

Fecal sludge managing organizations need to be visible, trusted by the community, and have quite sophisticated business practices. Operational decisions should be entrusted to the organization to enhance flexibility in tailoring services. For example, the Wastewater Association decided to outsource 11% (15/135) of their emptying jobs to a formal manual emptying group when they could not directly service the pits (due to inaccessibility or solid waste). The managing organization should have some autonomy to assess pits, set prices, choose appropriate suppliers, coordinate timing, and ensure customer satisfaction by resolving disputes. Government oversight should still hold the managing organizations accountable by monitoring high-level outcomes and customer satisfaction.

3. Build partnerships with different pit emptier groups

A ‘hybrid’ service delivery approach would combine the strengths of VTOs and formal manual emptying organizations. Partnerships also potentially promote payments from the VTOs to the manual-emptying organizations. A ‘switchboard’ model for linking customer needs to the most appropriate service provider (e.g., through a call center) has substantial potential to scale in Kisumu (with the Wastewater Association) and beyond.

4. Consider sanitation subsidies

Safe emptying services are often unaffordable and will likely require subsidies and political action to serve low-income areas. Financial incentives used in the study effectively promoted the expansion of formal pit-emptying services in low-income areas. Identifying the optimal incentive amount to support regulated pit-emptying service delivery models at scale in Kisumu and other locations would require accurate measurements of willingness to pay for pit-emptying among poor households. Further, identifying sustainable resources for these subsidies, whether from donor funds, government budgets, pro-poor sanitation surcharges imposed on utility bills, or higher fees charged to the wealthy (cross-subsidies), is an essential political consideration.

Pit latrine in a low-income settlement in Kisumu, Kenya. Photo Credit: The Aquaya Institute

5. Expand treatment capacity and regulatory oversight

The study emphasized the importance of increasing both Kisumu’s capacity and regulation of fecal waste treatment to ensure safe disposal or reuse. “Safe” pit-emptying services, considering the full sanitation lifecycle, likely require the augmentation of Kisumu’s fecal sludge treatment and disposal infrastructure. This expansion of treatment capacity may include additional staff, drying fields, and standards for chemical use (e.g., odor neutralizers) during pit-emptying.

These insights offer a means to expand safe fecal sludge management practices in Kisumu and other low-income urban areas. Learn more about the study by accessing Aquaya’s peer-reviewed publication or research brief.

Vanessa Guenther, Karen Setty, and Rachel Peletz are based in the US and work for the Aquaya Institute.

This research was awarded the Runner up under the Best original research abstract category, of the 2021 Sanitation Workers Research Awards.

Citation

Rachel Peletz, Andy Feng, Clara MacLeod, Dianne Vernon, Tim Wang, Joan Kones, Caroline Delaire, Salim Haji, Ranjiv Khush; Expanding safe fecal sludge management in Kisumu, Kenya: an experimental comparison of latrine pit-emptying services. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 1 December 2020; 10 (4): 744–755. doi: https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2020.060